Rethinking success and productivity

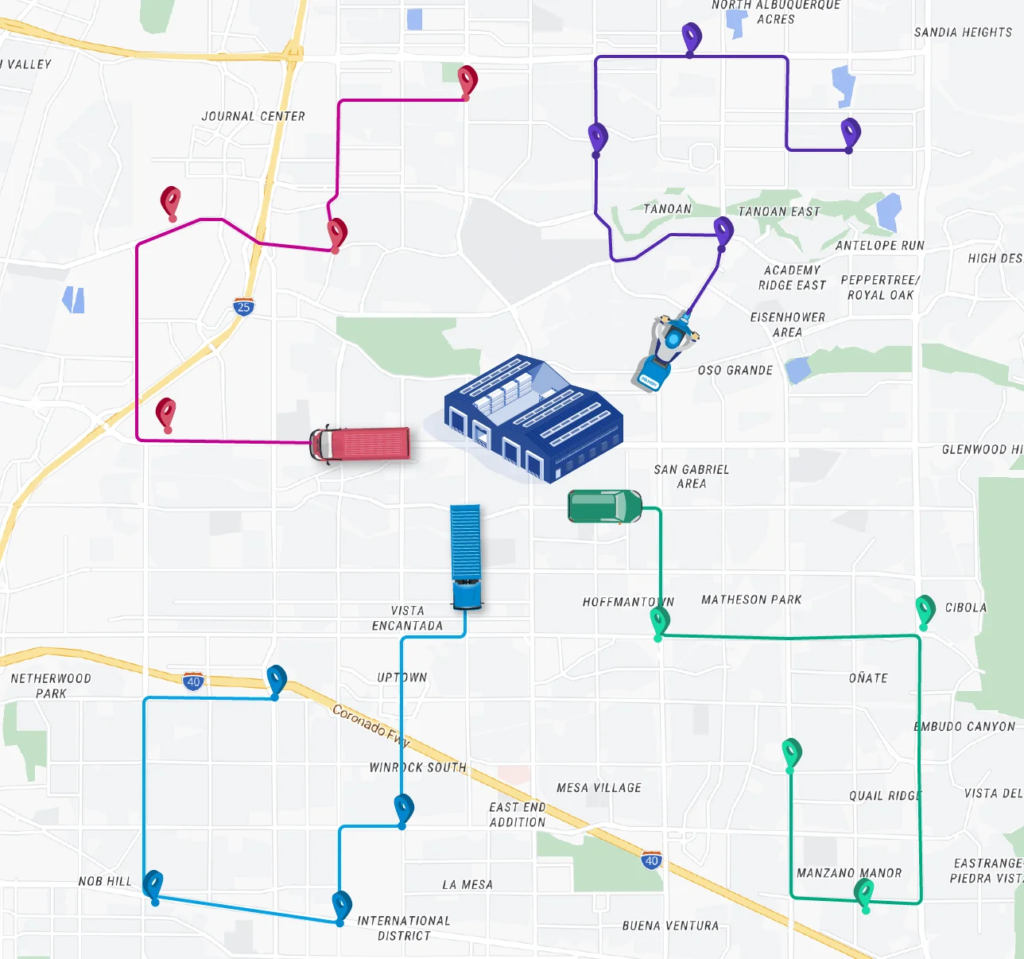

This experience is not the same kind of success story as those in the conventional sense. There were no profound inventions of new technology, no massive turns in market trends, nor were there any miraculous increases in workload. The main difference was that lanes were seen, detected, and assessed as a system rather than as isolated routes. As a result, the revenue increased, but the actual path to it came primarily from lane optimization rather than from working longer hours or pushing harder schedules.

This shift marked the first stage of increased revenue achieved through structural thinking rather than added effort.

At the time productivity seemed to be stuck. The company was already stretched to the limit, with tight workflows, and the idea of allocating more work to the current frame of reference seemed impractical. That was the situation: expanding without extra hours was not just a choice, it was the key. This led to a paradigm shift and to a different kind of mindset based on efficiency, optimization, and a realistic perspective on time.

This period forced a reassessment of time management as a limiting resource rather than a flexible one.

When we look back it is clear that this transition is not primarily about growth, but about the unnoticed inefficiencies that reshape results when they are left unattended.

Identifying hidden inefficiencies in lane structures

The initial awareness came from conclusions drawn from trends rather than from pure numbers. Lanes were run just because they were, and that was the way it went always. Choices were explained by custom, not achievement. Revenue figures were not bad at all, but the margin should have been better. The variance between the apparent performance and the real outcomes is often hidden in the very essence of the structures of the lanes themselves.

This stage formed the beginning of a broader historical overview of how operational habits influence results.

The optimization of the lanes did not start with the usual route changes, but with questioning the current assumptions. Some lanes looked to be productive because they were always done and therefore predictable. Other lanes were not run as they were thought to require more time or seem to be confusing. Yet, in a collective view, it became self-evident that predictability was not the same as efficiency. The same paths were consuming excessive time without bringing in the appropriate value.

The goal was no longer to maintain routines, but to deliberately optimize lanes based on contribution rather than familiarity.

Habit-driven lanes vs performance-driven lanes

| Evaluation factor | Habit-based lanes | Optimized lanes |

| Decision logic | Historical routine | Measured contribution |

| Time consumption | Often excessive | Controlled and intentional |

| Revenue impact | Acceptable but diluted | Aligned with margins |

| Operational fit | Disruptive in sequence | Smooth within workflow |

From lane adjustments to business optimization

Rather than posing the question of how to do more work, the attention was turned to doing work in a different way. The dissection of lanes was where the project started: inputs and outputs are time, revenue, variability, and operational drag. This change saw indivisible lane optimization morph into a broader business optimizer.

At this point, lane review became a core element of business optimization rather than a tactical adjustment.

Usually, the more revenue is thought of the more expansion. Nevertheless, the first income bump was not due to expanding but to right-sizing the business. The opening-up of the non-performing lane freed up more capacity for thought, scheduling shortcuts, and operational bandwidth. Productivity went up not because more work was done but rather through eliminating waste.

This early correction created the foundation for sustainable business growth without additional strain.

Time as the central constraint

No more work hours were left, so the management of time became the chief constraint. Every lane was analyzed not only with respect to gross income but also how it contributed to the general workflow improvement. Some lanes were bringing profits alone but problematic together. Others melded seamlessly with the whole process, thus creating smoother transitions and far less disturbance.

These evaluations gradually led to more streamlined processes across planning and execution.

This is the point where operational efficiency turned from a mere fashion phrase into a concrete target.

Processes were automatically smoothed out when pain points were made visible. The dispatching was more peaceful. The planning was simpler. The overall workflow began to unite around fewer and better lanes.

At this stage, strategic planning replaced reactive decision-making.

Signals that a lane was harming workflow

- High individual revenue but poor sequence fit

- Excessive time variance between runs

- Disruption to planning and dispatch rhythm

- Increased mental load despite stable results

Stability before growth

The increase in revenue was a silent issue. There was no sudden spike in it. First, it was stable. There was less variability. Forecasting improved. Finally, then did the growth became apparent. This is usually missed in the recant dis business, but stability comes before scalable efficiency.

Only after stability did the organization begin to consciously maximize revenue.

The historical analysis of this period shows a pattern common in many operations. Growth doesn’t stop because resources are scarce. It halts due to the mistreatment of them. Lane optimization was the thing that put it right. It ensured efficient resource allocation without adding the pressures of time or staffing.

Impact of stability on revenue outcomes

| Operational state | Variability | Forecasting | Revenue behavior |

| Pre-optimization | High | Reactive | Inconsistent |

| Post-alignment | Reduced | Predictable | Gradual increase |

| Optimized system | Controlled | Strategic | Sustainable growth |

Intangible gains and decision quality

The intangibles were one of the most unforeseen effects. The absence of extra hours affected the quality of decisions as well. Fatigue was cut down. Planning strategies were better. Productivity tips were no longer about taking shortcuts but were instead clearer. Instead of being the enemy, time became a friend and the mind improved.

These changes resembled practical productivity hacks, although they were rooted in structure rather than tricks.

Optimizing lanes also revealed the fact that the process optimization level of the revenue is directly affected by it. Small changes in setting, time, and choice accumulated over time. What seemed no factors when looked individually led to a meaningful transformation when the whole was considered.

Efficiency as alignment, not speed

The term efficiency, in this case, is not about speed. It is about getting things to be in line with one another. Lanes that were on par with the operational strengths of the company had better results with lower effort. Those that did not work were quietly sucking the value away.

In practice, maximizing revenue did not mean chasing after higher figures. It meant eliminating the friction between the input and the output. That is the core message of this history. Extra money without additional hours is not something hard to understand if you operate lanes as a system and not as habits.

List 2. What actually drove revenue increase

- Removal of underperforming lanes

- Better sequencing of remaining routes

- Reduced operational friction

- Improved planning clarity

Lessons that scale beyond one case

Business optimization most of the time sounds like a management team decision or something that comes from the top. This experience has shown the opposite side. The process was top-down and bottom-up at the same time: it comprised simple observations, quick fixes, and rigid assessment. The workflow was fruitful because it was intentional.

Looking back, the most marked change was the fact of no longer holding the belief that growth needs more time. With the absence of that assumption, the road to efficiency opened naturally. The lane optimization was merely the method through which that belief was tested and disproven.

No unique historical record exists in this regard, however, it can be easily repeated. In places where time feels fully occupied and progress feels halted, very rarely is the answer to try harder. More often it is a matter of comprehending how the movements work, how the lanes drain, and how the productivity benefits from the simplification of matters.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is lane optimization in practical terms?

Lane optimization involves seeing routes not as a set of independent entities but as part of a whole, therefore giving precedence to time, revenue contribution, and workflow impact above influence or routine.

2. In what way is revenue generated without the addition of any working hours?

Revenue rises due to the removal of inefficiencies, the elimination of underperforming lanes, and the realignment of remaining routes with operational strengths.

3. What made predictable lanes sometimes less efficient?

Predictability often covered up true costs, such as time overruns, workflow disruption, and reduced margins that were not visible in surface-level results.

4. How did time management make an impact on the process?

Time management acted as a hard constraint, forcing decisions to focus on quality, sequencing, and operational fit rather than on work volume.

5. How does lane optimization influence productivity?

Productivity improved through the reduction of operational drag, clearer planning, and fewer disruptions, not by working faster or extending hours.

6. Is lane optimization a one-shot fix or a continual process?

It is a continuous process that requires regular review to stay aligned with changes in conditions, demand, and operational capacity.

7. What was the biggest non-financial advantage of this strategy?

Key intangible benefits included improved decision-making, reduced fatigue, and stronger strategic thinking alongside financial gains.

8. Can this method be applied to businesses aside from logistics?

Yes. Any operation constrained by time and built around repeatable processes can apply system-based optimization in a similar way.